Your cart is currently empty!

Eye contact is a critical component to engage your audience. It makes the connection between you and your audience. If you don’t make eye contact with audience members every so often, they’ll start to drift. They’ll miss your message.

As speakers we need to make sure each and every member of the audience feels spoken to. It isn’t enough to make just to make eye contact with everyone in the room, but it needs to be often enough that they feel engaged the entire time. Frequent eye contact is the way you keep their concentration and interest.

Divide and Engage

Divide and Conquer is a winning strategy in various arenas of battle. We can use a similar strategy to create the impression for everyone that are being spoken to directly. I call this the ‘divide and engage’ strategy.

The principle is that we divide the room into sections or zones. We divide our attention among these zones. With some simple strategies, we can optimize our gaze to keep everyone engaged and alert. It can even guide us when we cannot see the audience, for instance because of the spotlights blinding us.

Six. That is the maximal number of zones we’ll create in the room. Most of the time, we won’t even need that many. Unless you are stepping on stage in a very large theater or stadium, you won’t need more than that.

How everyone can feel engaged

You might be wondering how everyone in the audience is going to feel spoken to, if we divide the room into so few zones. Assuming we are clever about how we divide the room into zones, it will work. It’s a matter of physics and human psychology.

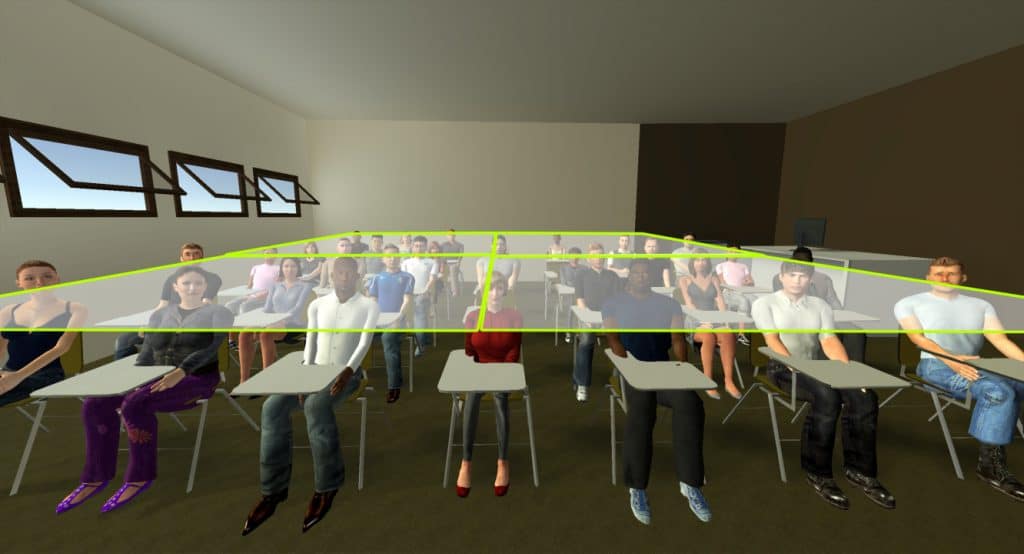

If you are directly in front of a person at a short distance, it is pretty clear where they are looking, but the further you’re back, the harder it is to tell. The potential points of focus for the other person is basically a cone going outward. Anyone seated in that cone of possible focal points is likely to feel like you are making eye contact with them. So, at a distance, you’ll be making eye contact with many people, even if you are focused on a single individual.

Another factor is we, as humans, aren’t that accurate at telling where people are looking. We tend to err to the side of believing the other person is looking at us. Combined with the physical cone of uncertainty, it creates an even larger area of people who feel as if you are speaking to them via your eye contact.

Dividing Strategies

How we divide a room depends on the room. There are three basic configurations we consider, which cover the majority of the venues you are likely to encounter. These are: the rectangular room, the long U and the wide U.

The rectangular room we divide into either 4 zones or 6. This basically comes down to size, shape, and layout. If the room is very large, then divide into 6. Generally the widest axis is divided into 3. Often the setup of the audience dictates how we divide the room. Aisles create spacing and natural breaks for zones. Here are some examples.

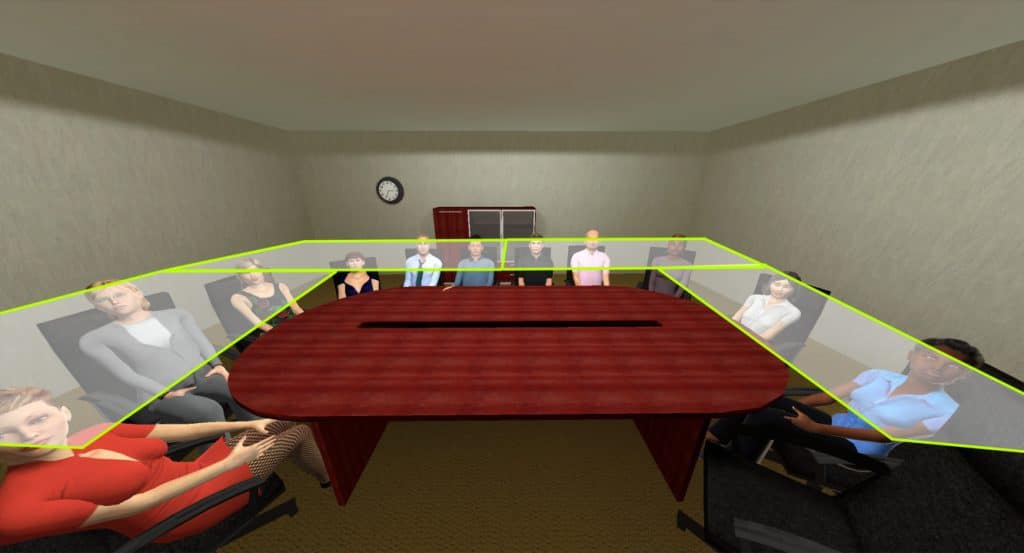

The long U is a common shape of meeting rooms in corporate offices and small hotel meetings room. The speaker is found at one end of a U or inward facing circle of tables. Depending on the size of the sides, we’ll usually divide the U into 3 or 5 zones, by dividing the long sides of the U in two. In rare cases dividing the head of the U might be needed, like if vitally important people are seated there.

The wide U is similar to the long U, but more challenging for the presenter. In the wide U you are in the middle of one side, instead of on the end. This is common in places like board rooms and smaller meeting rooms. This setup requires you to look to extremes to both sides and it is very easy to end up with audience members feeling ignored. Usually the most important people will be across from you, but you should engage everyone. It is also hard to keep your voice clear and understandable for everyone, especially if you are seated.

Zone Patterns

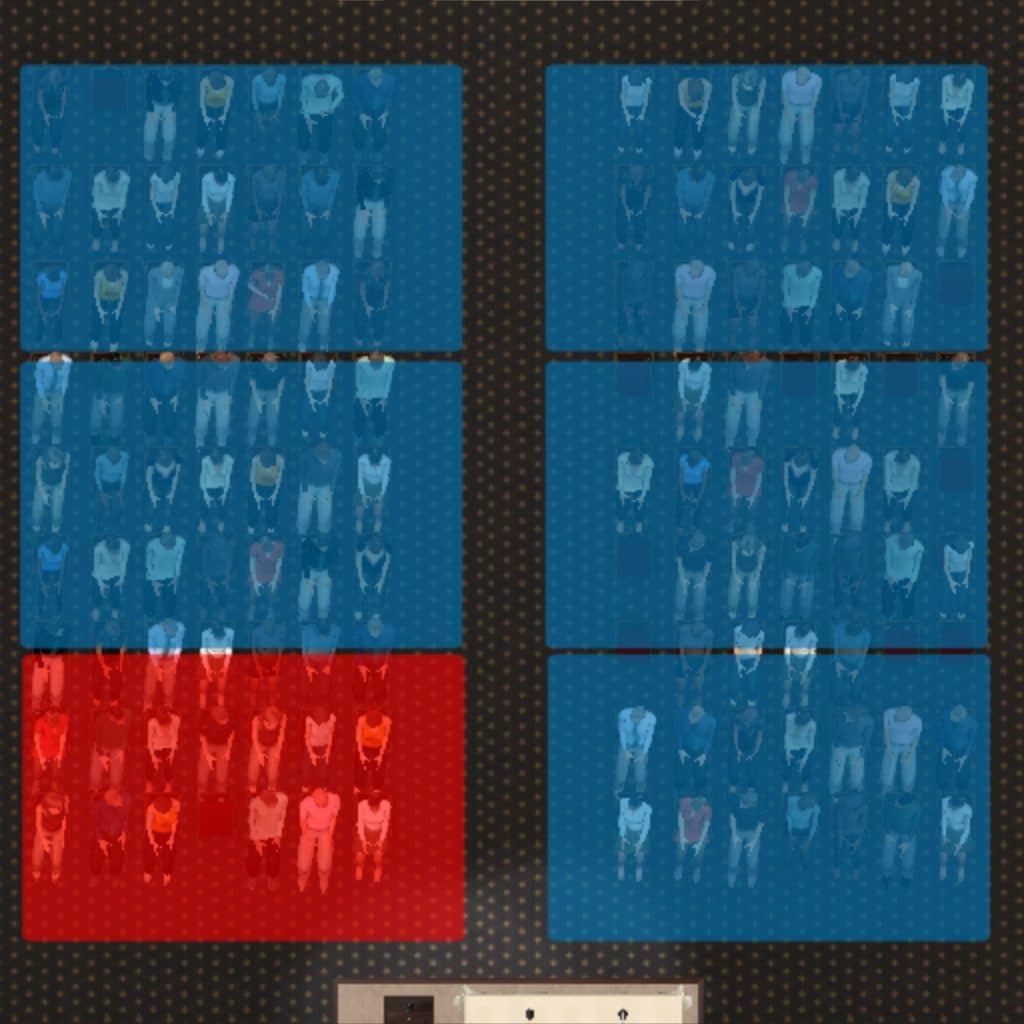

With our zones defined, we still need to consider how to manage our eye contact. We generally want to accomplish two tasks: dividing our eye contact evenly across the zones and making frequent eye contact with each zone. We don’t want it to feel rushed, but we also don’t want anyone to go too long without eye contact.

The easiest way to accomplish this is to simple say a couple of sentences to a zone, maybe composing a concept. Then, we move on to the next zone. For those of us who have issues with speaking too fast when stressed, this can also help us better pace our talk. It provides a healthy break. We just keep this up, delivering a few sentences to a zone and then moving to the next.

The pattern you pick to use depends on the venue. In the wide U you might go in a circle or the ‘windshield wiper’ method, but in a rectangular room you probably need more of a zig-zag. Since you want everyone to feel frequent eye contact, choose a pattern that moves your gaze around. A benefit of mixing it up is your eye contact will cross zones during movement and you’ll get extra benefits from the cone of potential eye contact.

Train to internalize

Engage your audience, the whole audience, with eye contact. This divide and engage strategy presented is fairly simple to learn, but on the day of your big speech your aren’t likely to use it effectively if you don’t practice. It is a skill that requires training (see this post on why public speaking is a craft). If you have not internalized the skill of divide and engage through practice, everything else, like stress and remembering your speech itself is going to override your good intentions. With some practice it can become natural.

Our product Virtual Orator is an easy way to get the practice required to internalize the Divide and Engage strategy. You present to your virtual audience, in whatever shaped venue you choose. Afterwards you get feedback on how you did. Did you skip one zone? did you only engage a zone occasionally? You can look at the performance data in a number of ways: how evenly your eye contact was distributed, how frequent, or how long a zone went without contact. This helps you find your deficits and internalize a good pattern.

Dr. Blom is a long time researcher in the VR field. He is the founder of Virtual Human Technologies, which applies VR and avatar technologies to human problems and helping better understand people. Virtual Orator exists largely because Dr. Blom wishes he had had such a tool instead of the ‘trail by fire’ he went through learning to speak in public.

Leave a Reply